Rethinking Ergonomics: More Than Your Office Chair, Keyboard and Mouse

Workplace strain injuries are among the costliest for maritime employers. Though often associated with office environments and equipment, many strain injuries occur outside of traditional office work environments. In a recent report on workplace safety1, overexertion – which includes strain injuries – cost employers $12.8 billion in 2023, accounting for nearly a third of all injury costs.

As an employer, reviewing your processes with an “ergonomic eye” can help identify opportunities to minimize the risk of these costly injuries, while improving the productivity, quality, and morale of your workplace.

A Brief History of Ergonomics

Ergonomics has a deep and long history in industrial and manufacturing environments. Derived from the Greek words ergo (meaning “work”) and nomics (meaning “natural laws”), the word ergonomics first entered the modern dictionary in 1857 by Wojciech Jastrzebowski.

Ergonomics originally focused on improving work efficiency and human engineering of complex machines and weaponry. Early manufacturing pioneers such as Frederick Taylor, Henry Ford, and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth utilized many ergonomic principles to improve work processes and make their employees more productive and efficient.

Taylor found that he could minimize fatigue and triple employee productivity by providing shovels of different sizes and weights based on the specific job tasks and work demands, replacing the previous “one size fits all” approach which forced the employees to adapt and be inefficient.

The Gilbreths were the first to develop “time and motion study”. By studying a worker’s motions and eliminating unnecessary steps and actions, the Gilbreths were able to reduce the number of back bending motions in bricklayers by 75 percent, allowing the bricklayers to increase productivity by 290 percent.

Henry Ford’s production lines used two ergonomic principles: bring work to the employee’s waist level to reduce unnecessary bending, and use machines to lift heavy objects to minimize worker fatigue.

Today, ergonomic science is used in a wide variety of applications. These include Health and Safety Injury and Illness Prevention Programs, Lean Six Sigma work efficiency and process improvement initiatives, Human Systems Engineering and design of military systems, industrial design of consumer goods, and human error/computer interaction of electronics and software.

Five Ergonomic Risk Factors to Consider at Your Facility

By designing work based on “internal productivity” (i.e., not overburdening or fatiguing the employee, allowing them to produce more output with less effort), waterfront employers can optimize the efficiency and quality of their processes while minimizing the risk of costly workplace injuries to the back, shoulders, arms, and knees.

When reviewing a job with “ergonomic eyes”, we should ask ourselves, “Would I do perform the task this way?” By looking for ergonomic risk factors (known as conducting a risk assessment), we can identify ways to improve jobs and reduce the risk of injury.

There are five main ergonomic risk factors to consider when evaluating a job:

- Awkward or static work postures such as bending, reaching or twisting with the neck, back, arms or legs. Awkward positions put the muscles and tendons at mechanical disadvantages, making them weaker. Static or stationary positions rob the muscles of needed oxygen, resulting in fatigue. Static positions require more recovery than dynamic motions.

- Forceful exertions such as lifting, carrying, pushing, pulling or gripping may overload muscles and increase fatigue.

- Vibration to the hands and arms from grinders, sanders, needle guns, chipping hammers, impact wrenches or chainsaws can slowly rob the body of much-needed blood flow and result in injury to the blood vessels, nerves or muscles.

- Repetitive motions of the wrists, arms, back, neck or knees occur from repeating the same motion repeatedly at a fast pace with little variation in the task. Frequent repetitive motions slowly fatigue the muscles and decrease productivity.

- Contact stress occurs when there is continuous contact or rubbing between hard or sharp objects and surfaces and sensitive body parts such as the fingers, palms, elbows, thighs, knees or feet. The contact creates localized pressure that reduces blood flow, nerve function and movement of tendons and muscles.

Identifying Ergonomic Risks with the Stoplight Method

Maritime employers combat the above risk factors by implementing a simple and effective three-step approach to ergonomics, developed by ErgoHP LLC:

- SEE ergonomic risk factors on your job

- SOLVE issues by implementing solutions

- SHARE and document successes with others

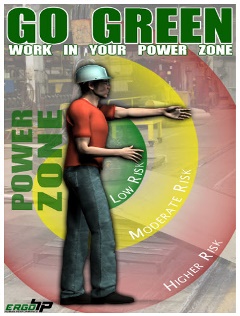

One easy method to SEE ergonomic risks is to use the stoplight method, GoGreen Work in Your Power Zone TM, also developed by ErgoHP LLC. This method, which uses three circles or arcs around the body to identify “work zones”, can be taught to employees and supervisors within minutes to be able to conduct a self-risk assessment.

- The Green Zone is an arc

from mid-thigh to shoulder height and is the length of a forearm held horizontally to the body. This zone is the lowest risk and has the maximum strength capabilities.

from mid-thigh to shoulder height and is the length of a forearm held horizontally to the body. This zone is the lowest risk and has the maximum strength capabilities. - The Yellow Zone is an arc from the top of the head to knee height at an arm’s length distance from the body. This zone is medium risk and has moderate strength capabilities.

- The Red Zone encompasses all other body positions that are beyond arm’s length and above the head or below the knees. This zone is high risk and has weak strength capabilities.

The location of the hands when working determines the work zone location. For example, standing at a bench grinding a steel plate would be the green zone, whereas standing on a ladder working overhead or crawling through a bilge would be red zones.

The basic goal of the GoGreen Work in Your Power ZoneTM is to work in the green and yellow zones for the majority of the workday. When working in the Red Zone, employees should stop and ask themselves questions such as, “Do I need help? Can I get in a better position? Is there a tool or equipment I could use to get me in the yellow or green zone?” The goal is to minimize or avoid red zone positions that quickly fatigue the body, reduce performance, take more time to complete, and increase the risk of an injury.

Next time you walk around your facility, use the GoGreen concept and count how many times you see your employees working in the green, yellow and red zone positions.

Train Your Ergonomic Eye as an Employer

You now have a better understanding of how ergonomics clearly transcends the office environment and has real application in shipyards, marine cargo handling facilities, and marine construction settings. By training your ergonomic eye to identify and address the risk factors outlined in this article, you’ll positively impact the safety of your workplace and your company’s bottom line.

Next month, we’ll discuss how the body becomes injured in various workplace conditions – and what you can do to prevent it.

1 2023 Liberty Mutual Workplace Safety Index. (n.d.). Retrieved September 26, 2023, from https://business.libertymutual.com/insights/2023-workplace-safety-index/

SEE, SOLVE, SHARE and GoGreen Work in Your PowerZoneTM images and materials are © 2023 ErgoHP LLC. For permission to use them in your facility, please contact Ben Zavitz at brzavitz@icloud.com.