Workplace shoulder and back injuries are a significant cost for maritime employers. Muscle-related strain injuries are a leading cause of injuries for the maritime industry and generally account for one-third of the workers’ compensation spend. The back and shoulder are two of the main body parts that are frequently injured. To prevent these types of injuries, we need to understand the risk factors and the strategies to minimize or prevent them.

Understanding Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder is a “ball and socket” joint that is formed by the shoulder blade (scapula), collar bone (clavicle) and arm bone (humerus). The shoulder is very mobile and can move in a wide variety of directions and motions. With this great mobility comes instability. To support the shoulder, there are a wide variety of muscles and ligaments. The primary muscles are the deltoids, which allow the arms to move forward, sideways, and backwards, and the rotator cuff, which is made up of four individual muscles and helps to stabilize the shoulder joint and aid in various shoulder motions. Fluid-filled sacs, called bursa, help to reduce friction and lubricate the joint, allowing tendons to glide freely. Two common shoulder injuries include tendonitis (inflammation of muscle tendons) and bursitis (inflammation of bursa).

Understanding Back Anatomy

The back is a curved column of individual bones, called vertebrae, that provide load bearing support for the spine in four distinct regions: neck (cervical), middle (thoracic), lower (lumbar) and tailbone (sacrum).

Through the vertebrae runs the spinal cord, which transmits information from the brain to your arms and legs. Between the vertebrae are discs that act as “shock absorbers”. Discs are composed of two parts: a tough outer ring and a soft inner “gel” core.

Damage to the disc can cause the “gel” core to pinch a nerve in the spine and cause leg pain. This is known as herniated disc and the resulting leg pain is called sciatica.

There are numerous layers of muscles and ligaments that support and stabilize the spine and supports the foundation of our entire body.

Ergonomic Risk Factors for Shoulder and Back Injuries

As I discussed in a previous Longshore Insider article, there are four main ways the body can become injured: high force from a single event, low force that is frequently repeated, low force that is constant or static, and cumulative loading over time without enough recovery.

The three primary ergonomic risk factors for shoulder and back injuries include:

- Awkward postures (bending, reaching and overhead work)

- Forceful exertions (lifting, pushing, pulling, carrying)

- Duty cycle (the number and total time an activity is performed vs. the amount of available recovery time)

Strategies to Minimize Shoulder and Back Injuries

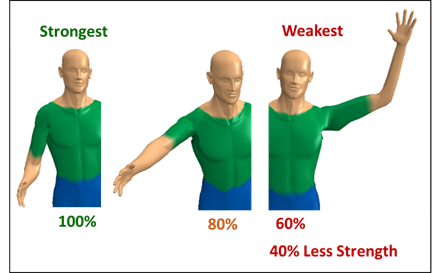

The human body works by a series of levers and pulleys controlled by muscles, tendons and bones. Mechanical advantages make some positions stronger than others. For instance, working with your elbows above your shoulders or reaching at an arm’s length reduces your shoulder strength by 40%. Back bending and reaching can reduce your lifting capability by 80% when the reach increases from 10” to 30”.

Here are a few tips to help reduce your risk of injury.

1. Minimize time in the “red zone” by designing and planning your work ahead of time

planning your work ahead of time

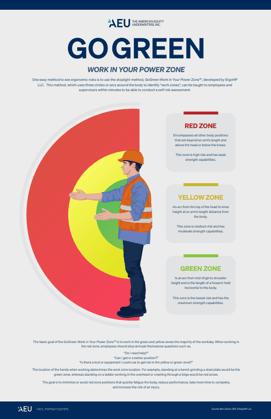

Review jobs prior to starting to find ways to get in a better and safer position. Use the Go Green graphic (see right, click to enlarge) to help identify positions of higher risk and less strength capabilities. Keep red zone postures to less than 50% of the work day.

Practical solutions to get you in a better position include:

- Use staging, step ladders or platforms to minimize extended reaches in the red zone by elevating you closer to the work (hands in the yellow zone).

- Tilt or rotate tables and stands to allow the work to be positioned closer to you.

- Use carts that eliminate the need to carry heavy or awkward objects, materials or equipment.

- Reduce the weight of the object by carrying lighter objects (e.g., two small paint cans vs. one large), substituting a heavy material for a lighter one (e.g., steel vs. aluminum), or using a lightweight jig or template in place of the actual equipment (e.g., use a 5 lb jig instead of 30 lb part when locating mounting positions and orientation of equipment in the overhead).

- Identify alternative uses of, or improvements to, current equipment (e.g., use a pneumatic cylinder to open machine doors, or having removable sides on a metal container to allow employees to remove heavy materials without reaching or having to lift the material over the 36” high side).

2. Minimize forceful motions

- Use mechanical assistance when lifting, carrying, pushing or pulling heavy or awkward objects.

- Use good body mechanics when lifting, pushing, pulling or reaching.

- Face direction of force when pushing and pulling to use large strong muscles, instead of pulling, pushing or lifting from a sideways or twisted position.

3. Minimize red zone positions and jobs, when possible

Sometimes it may not be feasible to eliminate working in a red zone position. When this happens, consider using some of these techniques:

- Rotate between red, yellow and green zone positions every one to two hours. Limit red zone positions to less than four hours per day.

- Take micro-pauses of three to ten seconds to drop your arms and get blood flowing back into the muscles from overhead work or stationary positions. Stand and reach overhead after prolonged periods of back bending.

- Keep your shoulders down and back (i.e., “packed” and in their sockets) to stabilize the shoulder and make you stronger when pulling, pushing or lifting at or above shoulder height.

- Tighten your abdominal and core muscles (10 to 25% effort) to stabilize and brace your body when reaching or twisting in the red zone positions.

- Use an “arm support” to rest your elbows on when working in the overhead (e.g., overhead welding).

Remember, prevention is the key; take the time to evaluate your workplace and implement some of the solutions above. Soon, we’ll share an article on strategies to protect aging workers from overexertion injuries.

GoGreen Work in Your PowerZoneTM images and materials are © 2018 ErgoHP LLC. For permission to use them in your facility, please contact Ben Zavitz at brzavitz@icloud.com.